November 30, 2010

Just returned from a snowbound weekend in Copenhagen - a city which offers a generous miscellany of transmedial and synaesthetic sensations at the moment.

GL Strand features an extensive three floor retrospect of visual art by David Lynch. His visceral and violent work brings to mind both Francis Bacon and Paul McCarthy, though, primarily, Lynch's own films. A specially composed soundscape - a kind of rumbling, ambient white noise - contribute to the malevolent moods charted across the paintings, photographs, drawings, and experimental short films. Another exhibition which triggered cinematic associations was Bob Dylan's "The Brazil Series" at the National Gallery, featuring 40 recent paintings. In common with Dylan's songs, this painterly work is instantaneous, colorful and pregnant with characters and narrative.

The main event, however, was the ambitious Anselm Kiefer retrospective at Louisiana, which features 90 works from 1969 until today - sculptures, paintings, and photographs. On Saturday December 4, Louisiana also hosts a one-day symposium on Kiefer titled "Totalitarianism and Contemporary Art." The exhibition is on till January 9. -HG

October 28, 2010

This week sees the publication of Paperweight, a newspaper devoted to visual and material culture, whose aim is to provide "an alternative space to the journal article, the book, the exhibition catalogue or the gallery" as well as to "promote the work of visual and material culture to as broad an audience as possible." The first issue can be purchased through the newspaper's website and features essays by among others Marq Smith and Øyvind. -A.G.

October 24, 2010

If you're in Oslo on Thursday be sure to catch Eyal Weizman's lecture "Political Plastic." -Ø.V.

October 6, 2010

New Novel

Congratulations to Øyvind, whose third novel Sekundet Før is out now! (on Tiden Forlag). Those who are familiar with his scholarly work will surely recognize some thematic concerns (pertaining to contemporary visual culture, the circulation of images, and the production of affect) that crisscross the spheres of fiction and criticism. Øyvind will be reading from his book tonight at Landmark, Bergen Kunsthall. An interview with the author is published here. -A.G.

September 28, 2010

Seminars in Oslo and Copenhagen

It has been a long weekend of seminar activities. On Friday, the 2010 FORART lecture took place at the University of Oslo, and I had been invited to be on a panel at The National Museum of Art the following day. The Institute for Research within International Contemporary Art is an independent organization dedicated to supporting interdisciplinary research activities and publications, and this year’s main speaker was Mark B.N. Hansen, professor of literature at Duke University and the author of several influential books that over the last decade have become touchstones in media theory, for instance New Philosophy for New Media (The MIT Press 2004) and Bodies in Code (Routledge 2006). The title of Hansen’s talk on Friday was “Recording (for) the Emergent Future, or Data and Experience in 21st Century Media,” a dense but fascinating post-phenomenological account of the experiential dimension of social media, their specificity, and how they might be conceptualized as apparatuses for exploring “the texture of embodied living as it happens.” The theme for the Saturday afternoon panel was “Creativity and Mediation from Husserl to Whitehead and Back.” It was chaired by Ina Blom (University of Oslo) and featured – in addition to Hansen’s lecture – prepared responses by Eivind Røssaak (National Library) and myself. Through a critical engagement with the philosophy of among others the late Husserl, A.N. Whitehead, Eugen Fink and Bernard Stiegler, Hansen addressed the problem of the new in relation to contemporary media and their production of connectivities rather than content.

On Sunday Øyvind and I flew down to Copenhagen, where we had been invited by the Department of Arts and Cultural Studies at the University of Copenhagen to participate in a symposium on visual culture studies in the Nordic countries, to present Nomadikon to an audience of master students in visual culture and, finally, to introduce our journal Ekphrasis to our colleagues from Denmark and Sweden. It became a long but delightfully stimulating and eventful day, and our panel – which was expertly moderated by Hans Dam Christensen and which consisted of Helene Illeris, Karl Erik Schøllhammer, Gunhild Borggreen, Max Liljefors, Anders Michelsen, Øyvind and myself – covered a whole batch of interrelated topics pertaining to the future development of Nordic visual culture studies: the notion of “the Nordic” in relation to the global, the national and the local; visual specificity; transdisciplinarity; visual culture and its object(s); the critical potential of visual studies; and the concept of research within an institutional framework that some have come to see as “post-academic.” Thanks to our eminent hosts Gunhild and Anders for organizing this wonderful seminar. -A.G.

September 20, 2010

Saving Private Reels

I spent the weekend in Cork, attending the conference Saving Private Reels: On the Presentation, Appropriation and Re-contextualisation of the Amateur Moving Image, expertly convened by Laura Rascaroli, Barry Monahan, and Gwenda Young, who had gathered scholars, archivists, and artists for an intense, stimulating and unusually varied three-day program. As expected several of the presentations touched on the conceptual multiplicity of ”the archive” and the various ways in which this word has been, and continues to be, rethought, but the conglomerate of participants in Cork made many of the ensuing discussions particularly interesting, I think. To many who attended the archive is a very specific physical location, more or less contested by the shifting politics and poetics of preservation. And to many others the word is, of course, a recently revitalized metaphor (Derrida, Foster, Mitchell) that offers a way of thinking about images and the way in which they appear and circulate. Thus there were presentations on YouTube as a form of archive, where ephemeral snippets such as the charmingly funny David after Dentist constitutes an image with what Lauren Berliner described as a ”life cycle.”

That kind of image makes for a pretty strong contrast with the kind of material images we find in the private reels that gave the conference its amusingly connotative name. During an evening event in the beautiful UCC aula, ”Capturing the Nation: Irish Home Movies, 1930-1970,” we were shown recently digitised footage from the collections of amateur film at the Irish Film Institute in Dublin. The screening was accompanied by Elaine Brennan on piano, a fact that impacted the experience greatly; the music was extremely resonant and attentive to the images we saw on the screen. It also transformed some moments that could be considered banal into moments of arresting beauty (at least to me).

The way that the amateur image raises questions concerning permanence, preservation, distribution and circulation, as well as the way in which it negotiates between private and public spheres and shape individual as well as collective memories, were not only topics central to the proceedings, then, but rather a problematic that kept appearing in foreseen and unforeseen ways throughout the conference – which is a great quality. I came to Cork to present a chapter from my forthcoming book on the Zapruder film, and couldn’t have hoped for a better audience with which to discuss that film’s peculiar history, both during as well as before and after my panel session. Many presentations and events could have been mentioned, but I’ll settle with two. Patricia Zimmerman’s keynote address on Saturday, ”The Home Movie Archive Live,” was as passionate as it was rich on ideas, with its invitation to reconsider the amateur image. Quoting Hayden White’s great phrase, ”The past is a place of fantasy,” Zimmerman provocatively called for a notion of ”dialogic archives,” for a movement from ”necrology” to ”live,” from ”dead” to ”living,” from ”denotative” to ”connotative.” Zimmerman reimagined the amateur image as ”a vector of constant movement,” ”a node of complex transnational movement,” and was inspired by a kind of contemporary live performance in clubs, installations, and bus tours that enlivens the amateur image in ”spaces of conviviality” rather than in ”worship of the object.” Zimmerman wanted the audience to let go of the fixation on ”the lost object” and called cinephilia a kind of ”celluloid nationalism.” The presentation was thought-provoking and inspired a certain amount of worry among some of the attendants, and ferocious scribbling in notebooks among others. The other paper I’d like to mention is Mark Neumann’s very different talk on 8 mm footage shot by a family on vacation on Route 66 in 1947. Neumann described how the film we saw represented a ”re-enchantment of the landscape.” What do you do when amateur film lacks context, when there is little knowledge about the circumstances that surround what we see? Then one turns it into ”an interpretive conundrum,” Neumann eloquently suggested. The evocative footage made me think back on my master’s thesis written a decade ago, on ”the journey narrative” in American fiction, and on my first drive on Highway 1 earlier this spring, for which Asbjørn had brought a carefully composed playlist. That trip came to mind when Neumann asked: If there had been a cd player in the car the Jackson family drove back in 1947, what would they have listened to? –Ø.V.

September 16, 2010

Urban Images

On September 9-10, the Oslo National Academy of the Arts hosted a symposium titled Urban Images: Re-imagining the City through Moving Images. Tom Gunning was the opening act, discussing the relation between city space and modernist forms through the figure of the montage; Edward Dimendberg and Giuliana Bruno gave inspired talks on the interactions of film screens and architectural exteriors; and conference organizer Marit Paasche gave a rich analysis of the films of Hito Steyerl. The most entertaining talk was delivered by Beatriz Colomina, shedding new light on multi-screen projections by relating them to war room technologies rather than gallery spaces - and also offering a rare opportunity to see Glimpses of the USA, first shown at the Moscow World's Fair in 1959.

The conference included three intriguing artist presentations; Bull.Miletic presented an Anne Friedberg-influenced reading of their work on the history of revolving restaurants; Andreas Bunte showed exerts from a series of his recent 16 mm films exploring the spaces of modern utopias; and Judy Radul discussed her intricate exploration of the theatrical space of the court room. My own presentation addressed how the relation between the city and the country are mapped-out in three films by Claude Lanzmann -Why Israel (1973), Shoah (1985) and Tsahal (1994) - arguing that this trilogy is marked by a deep asymmetry in the way the relation between urban and rural spaces are used to evoke and erase memory.-H.G.

August 13, 2010

Visible Evidence XVII

I’m just about to head home from Istanbul after this year’sVisible Evidence conference, my first, which came to a close yesterday. The range and depth of the presentations made it an excellent experience, and thus this rather lengthy report. My notebook is dense with scribblings so it’s hard to single out particular panels or papers, and with three panels to choose from in each of the many daily sessions some tough choices had to be made. There has been a fair amount of rushing from one thing to the next, like Wednesday, when I sat down in the viewing library at the Bogaziki University to see Cayan Demirel’s disturbingPrison No. 5 1980-84 (2006), about the use of torture and ”Turkification” policies at Diyarbakir Prison after the military coup in 1980, and then ran straight over to the conference building to catch a panel on ”Documentary Discontents: Lessons from the Art World.” In the early moments of that panel I could not stop thinking about Demirel’s film, which contains testimony from several Kurdish prisoners, so it took me a while to get into Nicole Wolf’s beautifully written opening paper. I’m somewhat influenced by Wolf in acknowledging these circumstances, for her paper was one of the most elegant instances of addressing the significance of the situatedness of seeing – not least in gallery spaces of various kinds – that I have heard at any conference. Frances Guerin gave an attentive and sensitive reading of two of Esther Shalev-Gerz’s installations which revolve around ”the subject as listener and the image as mute.” Sound Machine (2008) and First Generation (2004) are acts of testimony ”where noone speaks,” Guerin observed, where ”the act of listening of the subject” is central.

The panel was smartly designed by Irina Leimbacher, who in the end was unable to attend, but whose paper was given by Alisa Lebow in her place. To me it was among the most thought-provoking of this conference. Leimbacher (in absentia) lamented the absence of reflexivity in contemporary documentary, and suggested that it had ”moved to the art world.” ”The art gallery has become documentary’s conscience,” Leimbacher (embodied by Lebow) suggested, in what must have been one of this conference’s most provocative statements. Leimbacher addressed this ”emigration of critical practice” by taking a closer look at Omer Fast’s The Casting (2007). In a comment after the panel, Chuck Kleinhans worried about the implications of this observation for how we are to conceive of documentary’s impact and role in society: Who enters the gallery? he asked, and who never goes there?

What we think of as ”documentary” has always been changing, and no less now than before. The first panel I attended on Monday morning made for what Michael Renov in a comment called a ”heady start,” as it sought to address the theoretical implications of the rise of so-called ”animated documentary.” Bella Honess Roe distinguished between what she called three ”functionalities” and sketched out a typology. All the presenters addressed the rather thorny question of indexicality, or in the words of Honess Roe, ”the insufficiency of the concept of indexicality in addressing the epistemology of animated documentary.” These gestures towards alternative conceptualizations inspired (animated) discussions that probably could have lasted the rest of the day, but at some point we had to find our way through the impossibly beautiful Bogaziki campus to have lunch at the Kennedy lodge (where I was fortunate enough to get a brief history of the University from a local who could tell me that the photographer and director Nuri Bilge Ceylan, who made the splendid Uzak (2002) and got the best director award in Cannes for Three Monkeys (2008) (which I have yet to see) had been a student here).

Theoretically dense was also a panel on French theory the following day that addressed ”the irreducibility of visibilities to statements.” Two of the presenters focused on Deleuze’s reading of Foucault, whereas the third brought in the increasingly omnipresent Rancière. This led to a debate in the audience on the implications of the notion of ”the sensible,” ”the sphere where the political is at stake,” in the words of panelist Manuel Ramos, for how we are to conceive of the documentary image. For a number of reasons there has been a very strong focus on the political at this conference, the culmination of which perhaps was Michael Renov’s paper ”A Poetics of Political Documentary,” which I unfortunately missed, since I was participating at another session. I came to Istanbul to present a paper on Werner Herzog’s use of reenactment, and before I gave my paper yesterday I had already heard brilliant presentations by Selmin Kara on the director’sLessons of Darkness (1990) and a fascinating talk on ”participatory reenactment” in ”juridical documentary” by Kristen Fuhs, who showed a clip from and discussed Emile de Antonio’sIn the King of Prussia (1982). The question of reenactment (and more broadly of documentary ”stylization,” as the lingua franca in documentary studies will have it) seems to me to arise at the intersection of the political and the aesthetic in a very profound way, and this, I think, was reflected in several of the papers here in Istanbul. de Antonio had sought to achieve a rough aesthetic, Fuhs observed, because the material demanded it. On her hand, Patricia O’Neill argued in an early paper on The Color of Olives(2006) that the film’s style (it includes several enactments of both past and present events) achieved something observational documentary cannot. These problems were (inevitably) very much with me when I watched Cayan Demirel’s film in the darkness of the campus viewing library, where oral testimony by prisoners was accompanied by drawings of the events in the prison, suggestive images of shadows of chained prisoners, and footage of empty cell corridors – the last of which was terrifying in a way that it’s really difficult to understand, let alone articulate.

All this in a city that leaves an impression on you in its own right, yet fortunately in a more soothing way. ”I have always preferred the winter to the summer in Istanbul,” writes Orhan Pamuk inIstanbul: Memories and the City (2003), which I have been reading before and during my stay in this stunning city: ”I love the early evening when autumn is slipping into winter, when the leafless trees are trembling in the north wind and people in black coats and jackets are rushing home through the darkening streets.” In Pamuk’s vision these streets and the people that move through them turn into shapes and lines of black and white, into a shadowy landscape. I have to admit that I felt a bit embarrassed carrying Pamuk’s book around, as his influence now seems to have become something of a cliché: I even saw him quoted in the restaurant reviews plastered on the walls of restaurants when I visited the Sultanahmet area. Be that as it may, his book’s beautiful descriptions of how he prefers the city during winter made me recall several gritty scenes from Bilge Ceylan’s 2002 film, all of which felt very distant in the summer heat the city presently sees. When I went to sleep one of the nights here, and found myself longing for a snowfall during the night, then, it wasn’t merely because the heat here is severly intense for a Scandinavian used to perpetual rain and sleet and snow, but because the depictions by the writer and the filmmaker had made me curious about that particular sight, by way of their stylizations of the landscape that has surrounded me these last few days. –Ø.V.

June 29, 2010

The 4th NECS Conference: Urban Mediations

I just got back from the 4th European Network for Film and Media Studies (NECS) conference, an annual event that this year took place in the magnificently visual city of Istanbul. The theme of the conference was “Urban Mediations,” and my impression was that a great many of the panels and papers stayed pretty close to the main topic, perhaps to a somewhat unusual extent for a conference this size (there were twelve sessions with seven parallel panels for each session). It’s actually only four (or four and a half) years since the foundation of NECS in Berlin in February 2006 – I can vividly recall the sense of cautious excitement that characterized that first meeting – and since then the organization has developed quite rapidly into something which already very much looks like an established institution.

The pervasive conference theme was aptly encapsulated in a talk by someone who – befittingly enough – is no stranger to cosmopolitanism himself. Thomas Elsaesser’s keynote address “In the City but Not Bounded by it: Spatial Turns and Lines of Flight” explored the concepts of “the cinematic city” and “the global city,” focusing among other things on recent changes in the relationship between cinema and urban space, as well as on the film festival as a dynamic intercultural force with the capacity to rebrand cities and impact the production schedules and marketing of international art films. Observing that cinema acts like “a cultural lubricant,” Elsaesser also dealt with the question of post-national cinema and “post-national nationalism,” arguing that European cinema should be re-contextualized within the framework of world cinema and that world cinema in turn should be understood within the context of the film festival and its connection to “new forms of sociality.” Listening to this lecture, I was reminded of Nicholas Mirzoeff’s talk in London about a month ago (mentioned in Øyvind’s entry of May 30), a part of which was likewise preoccupied with the relationship between urban space and visual fiction, although Mirzoeff’s argument also revolved around crucial matters of visibility/invisibility (the right to see/the right to be seen). Throughout the keynote in Istanbul I kept waiting for a reference to David Simon’s HBO series Treme,which, I think, wouldn’t have been out of place even in a talk abut art cinema and film festivals, but in terms of specific works Elsaesser mainly alluded to multi-narrative films such as Short Cuts, Magnolia, Crash, Chungking Express, Babel and 21 Grams.

Immediately following Saturday’s plenary was a workshop chaired by Malte Hagener on the very timely topic of “Teaching Specificity, Teaching Convergence.” Whatever conceptual term one prefers – “remediation” (Bolter & Grusin), “convergence culture” (Henry Jenkins) or “the post-medium condition” (Rosalind Krauss) – things are not quite what they used to be. “Is our self-understanding still disciplinary?” was the rather complex question that prefaced this discussion. Many of the participants pointed out that students no longer think along traditional lines of medium specificity in their personal lives as media users, whereas somewhat paradoxically, they actually do when it comes to taking media studies courses. For Janet Staiger (Austin), one of the five panelists, distinguishing between multiple meanings of the term “convergence” was a significant issue. Winfried Pauleit (Bremen) in his talk underscored the importance of film studies as a necessary platform for understanding new media, while Wanda Strauven (Amsterdam) discussed organizational changes in the curriculum recently undertaken at her home institution, where they had dissolved the film-television-new media triptych into more interdisciplinary entities like “media history” and “media theory.” Finally, Thomas Elsaesser seemed equally wary of both specificity and convergence, and he dismissed the teleological notion of convergence (the view held by some that the different media have evolved toward a kind of super-medium) as “profoundly misguided.” As for the state of the discipline of film studies, he also pointed out that there is currently a tendency – in the US in particular – for philosophy and art history departments to absorb cinema studies, now a “wounded animal” according to Elsaesser.

While the problem of teaching specificity/convergence is one that obviously cannot easily be resolved, the topic deserves further attention. Maybe a follow-up workshop next year?

London will be host to the 5th NECS conference, which takes place June 23-26 2011. -A.G.

June 19, 2010

First Issue of Ekfrase Out

The first issue of Ekfrase: Nordisk Tidsskrift for Visuell Kultur is out! -Ø.V.

May 30, 2010

The 2010 Visual Culture Studies Conference

As yesterday’s final session at the 2010 Visual Culture Studies Conference at Westminster University in London (co-hosted by Marq Smith, Joanne Morra and Nicholas Mirzoeff) ended cheers were called out for a new international society. In a roundtable discussion Stephen Melville had pointed out that a new association’s capacity to sustain itself depends on its ability to ”reimagine the university from within.” Again and again over the last few days the news that Middlesex University has decided to cut its Philosophy Department threw attendants into rightfully dismal discussions concerning what not only Visual Culture Studies but the University and higher education at large might look like in the future, in the age of what Jeremy Gilbert called ”the University Industrial Complex.” One of the catchphrases of the conference turned out to be Adrian Rifkin’s warning to address and work with instead of avoiding a widely shared ”sense of perplexity” in the times in which we find ourselves. A society now exists, but it remains to be seen of what shape it will be. Another conference in New York City in 2012 should offer a few answers and very likely a number of new questions.

Many of the papers at the conference addressed the present political, historical and cultural moment in diverse ways. W.J.T. Mitchell called for a ”racialization” of academic discourse. Keith Moxey drew our attention to various attempts to periodicize the present moment. And Nicholas Mirzoeff – after having provided the audience with the most entertaining moment of the conference, a clip from a scene from David Simon’s new Treme (HBO) in which John Goodman delivers a notorious You Tube address – described the need to ”reclaim the everyday” in contemporary visual culture. –Ø.V.

May 25, 2010

We are proud to currently have a still from Khaled Jarrar's Journey 110 on our front page. Khaled suggested that we publish a few words about the film, so that visitors to the page can find out a little bit about it, and we'd like to follow him up on that: "In this short art piece, we see ordinary men and women placing plastic bags over their feet, pulling their clothing up to their knees, clutching their children to their chests, and setting off down a 110 metres long tunnel of sewage. This surreal and saddening sight is not staged. Jarrar’s short is shot in one of the few 'routes' through which Palestinians try to enter Jerusalem from parts of the West Bank. Shot during the month of Ramadan in a sewage culvert beneath Beit Hanina (a Palestinian neighbourhood of Jerusalem divided by walls and checkpoints), Journey 110 is visually haunted by half invisible bodies wading through fetid darkness to reach a distant light at its end. Jarrar reflects on a resonance with the socalled 'Journey of Light' associated with near death experiences: The 'Journey of Light' is often described as floating upwards peacefully through a long journey of intense darkness toward a narrow entrance in delivering light." -Ø.V.

April 26, 2010

Studies in Comics #1

The first issue of Studies in Comics (Intellect) is out, with a number of exciting essays. "This field is a model of interdisciplinarity and stands at the threshold of becoming a vibrant new area of teaching and research activity," Julia Round and Chris Murray write in their first editorial: "comics scholarship is well-placed to make an impact on the thinking of scholars in many adjacent fields, as well as on the general public, demonstrating the potential of comics to stimulate ideas, provoke emotions, and challenge convention." The journal seems likely to become obligatory reading to anyone interested in what's going on in comics theory. -Ø.V.

April 20, 2010

The Ambiguity of the Concept of Media

How do we delimit media studies, and what is to be gained from such a delimitation? The question is raised in the early pages of the Introduction of W.J.T. Mitchell and Mark B.N. Hansen's Critical Terms for Media Studies, just out from the University of Chicago Press. The editors turn to Wikipedia, and find that the entry divides media studies into two traditions: "the tradition of empirical sciences like communication studies, sociology and economics," and "the tradition of humanities like literary theory, film/video studies, cultural studies, and philosophy." "These conventions group into two categories," the editors suggest, "the empirical and the interpretive - which, though far from homogenous, designate two broad methodological approaches to media as the content of research" (viii).

Unsurprisingly, the strategy for this volume is somewhat different. "Rather than focusing on media as the content of this or that research program, we foreground a range of broader theoretical questions: What is a medium? How does the concept of medium relate to the media? What role does mediation play in the operation of a medium, or of media more generally? How are media distributed across the nexus of technology, aesthetics, and society, and can they serve as points of convergence that facilitate communication among those domains? Expressed schematically, our approach calls on us to exploit the ambiguity of the concept of media - the slippage from plural to singular, from differentiated forms to overarching technical platforms and theoretical vantage points - as a third term capable of bridging, or 'mediating,' the binaries (empirical versus interpretive, form versus content, etc.) that have structured media studies until now" (viii).

The Introduction goes on to stress the significance of seeing "media as an environment for the living," a conception that differs from that of "the medium/media as a narrowly technical entity or system": ”Before it becomes available to designate any technically specific form of mediation, linked to a concrete medium, media names an ontological condition of humanization - the constitutive operation of exteriorization and invention. The multitude of contemporary media critics who focus on the medium - and media in the plural - without regard to this ontological dimension run the risk of positivizing the medium and thus trivializing the operation of mediation. Whether this leads toward an antihumanist technological determination (Kittler) or the undending media-semiosis of Jay Bolter and Richard Grusin's 'remediation' (itself, fundamentally, a remediation of McLuhan), what is lost in the process is a broader sense of the existential stakes, of how these operations of mediation tie in with the form of life that is the human" (xiii).

Needless to say the book offers much food for thought, in engaging essays by an impressive group of scholars. -Ø.V.

April 5, 2010

If you're a student of visual culture and interested in images as sites of political conflicts, Copenhagen seems the place to be this upcoming weekend, as the city will host the seminar "Image Politics - to see is to destroy" from April 10-11. -A.G.

March 23, 2010

Some of us are back from last week's Society for Cinema and Media Studies conference in Los Angeles, "Archiving the Future, Mobilizing the Past," an event which also marked the 50th anniversary of this scholarly association. Øyvind and I were in a panel chaired by Arild Fetveit on Errol Morris's somewhat divisive documentary Standard Operating Procedure, while Henrik was in the panel "The New Documentary," which was chaired by Mattias Frey. My own paper was altered substantially from the version prepared for the cancelled Tokyo conference last May, mainly because I realized that my reading of Morris's film would benefit from a more comparative approach. So the title of the paper went from "Standard Operating Procedure and the Ecology of the Image" to "Explaining Ourselves to the Image: Ethics and Form in Morris, Folman and Haneke," in which I discuss what I call the forensic morality of S.O.P. with reference to the reconciliatory morality of Ari Folman's Waltz with Bashirand Michael Haneke's Cache. There was also another panel onS.O.P. called "Reframing Standard Operating Procedure" (with presentations by Bill Nichols, Linda Williams and Jonathan Kahana) that we unfortunately missed due to other commitments. But Henrik might share his comments here later. -A.G.

March 5, 2010

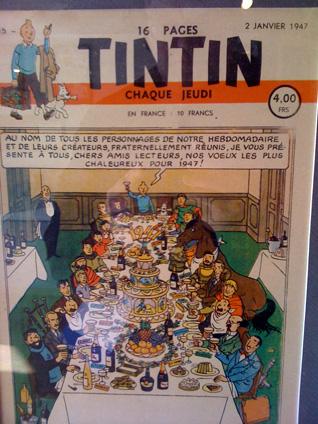

This week I had the fortune to spend an entire day at the Belgian Comic Strip Center in Brussels. Its permanent exhibitions are historically oriented (more information here), with a variety of highly interesting original objects on display. Having been an avid reader (if not ”mildly obsessed” is a more fit description) of Tintin as a child, I spent a luxurious amount of time looking at artifacts such as Christmas issues of the Tintin journal from the late fourties. I also happened to arrive just as a new exhibition on Tove Jansson opened. The better part of the afternoon was spent exploring the impressive research library on the ground floor, to which I’ll most certainly return in the future. –Ø.V.

February 25, 2010

Last Thursday I participated in the conference Imaging History - Photography after the Fact held at Hogeschool Sint-Lukas in Brussels. Organized within the framework of an interdisciplinary excavation project at the archeological site Sagalassos in southwestern Turkey, the event offered various perspectives on using photography as a tool for artistic research. As this context suggest, the presentations focused on the intersection of photography, archeology, and site specificity, asking how a visual engagement with places where events have passed without being recorded might help us to imagine and access those past events.

The day concluded with Magnum photographer Carl De Keyzer who talked about his recently finished project "Congo (Belge)." Exploring the remains of Belgian presence in Congo fifty years after the end of colonial rule, often with a strikingly surreal effect, Keyzer described his work as an ongoing effort to correct his own vision and idea of history. -H.G.

February 9, 2010

In the course of a couple of hectic and invigorating days a group of scholars (including yours truly) gathered in London to form a new research network, Visual Culture in Europe, last week. Our exquisite hosts were Marq Smith and Joanne Morra, editors of theJournal of Visual Culture, and visitors came from all over Europe (Spain, Italy, France, Croatia, Austria, Lithuania, Norway). We're soon going to have a web page up and running, and a number of exciting things are bound to transpire from this effort, of which I'll report in future posts. We're envisioning a questionnaire in the near future, in which we will invite scholars and others to present their thoughts about what "visual culture studies in Europe" is, or could be -- or should be.

A couple of pictures from the event below (thanks to Andre Gunthert): Top, from left, Marq Smith, Iain Chambers, Anna Maria Guasch, Joaquin Barriendos, Almira Ousmanova. Below, Marq Smith draws up a to do-list on the board. -Ø.V.

February 2, 2010

I'm just back from Angoulême, France, where I visited the International Comics Festival. It was the first time for me, so I was very fascinated by how the whole town was transformed by the event. One morning I noticed Guy Delisle sitting right across from me on the bus, and a few hours later I saw Thierry Groensteen at a Moroccan restaurant: It was a brilliant gathering of artists, fans, scholars, and newly interested, and I'd love to go back.

The most important reason I had for going, though, was that Joe Sacco had granted me an interview. His schedule was incredibly busy, so I really appreciated the fact that he sat down with me and answered every question with generous patience. I'm busy transcribing, and will post an excerpt in a few days; the conversation touched on a number of issues and addressed most of his works.

Sacco readers might be interested to know that a new piece is out, "The Unwanted," about African immigrants in Malta, in The Virginia Quarterly Review, which offers an excerpt for online readers. -Ø.V.

February 2, 2010

Last Thursday and Friday I was in Oslo for the inaugural workshop of the new research project "Conflicts and Negotiations: Gender and Value in Art and Aesthetics," with which I'm affiliated. This interdisciplinary project was off to a very promising start, and the seminar featured a range of papers and presentations, as well as some vibrant discussions, in an eclectic group consisting of literature scholars, film studies people and art historians. My own talk was part of my ongoing work-in-progress on the philosophy of disciplinarity and the notion of the transaesthetic, and on this particular occasion I posed the question "Is There a Transmedial Dispositif?" -A.G.

January 30, 2010

Last Monday the National Library in Oslo gathered a host of prominent scholars for the one-day conference The Ends of Photography: Photographic archives and research in a digital age. Charting the territory between archive politics and research theories of visual culture, the concept of the photographic image was addressed within the sobering contexts of copyrights, commerce and consumption. Matthias Bruhn from the Humboldt University in Berlin set the agenda by focusing on the legal and economic dimension of images. Noting that the world of digital images is anything but immaterial, Bruhn analyzed how every new mass media defines its own ecology of remembrance and oblivion.

John Tagg delivered a captivating presentation which took the filing cabinet and the catalogue, rather than the camera, as the basis of photographic meaning. Elaborating on "the archive machine" as a disciplinary apparatus, Tagg argued that despite its drive to organize the production and consumption of photographic images, the archive is always open to contestation. Following the collapse of police states and oppressive regimes across the world, counter archives have emerged, bringing into light what has been kept from view by engaging in a forensic archaeology.

The final speaker of the day, James Elkins, reflected on recent shifts in artistic practises and academic research brought on by the waning status of the photographic document as a source of knowledge, evidence and facts. As a consequence, photographers and scholars have become increasingly engaged with non-visual material. When cultural and interpretive contexts multiply, the image recedes, and the visual object comes to mean less than the role it plays in public life. Aptly summing up the day's discussions, Elkins concluded that the visual can possess knowledge, but it needs a lot of help to speak. -H.G.

January 26, 2010

"I'm not interested in a unique picture. I'm interested in something that refers to other pictures. The common thing about a camera is that you're supposed to technically overcome it and then it becomes a slave to your mastery and your subjective vision. I would rather let the camera and other people's pictures guide me."

This is how the American photographer and conceptual artist Christopher Williams described his work at an artist talk before the opening of For Example: Dix-Huit Leçons Sur La Société Industrielle (Revision 10) at Bergen Kunsthall. The exhibition is also the first major presentation of Williams in a Nordic context. My review is available at: http://kunstkritikk.no/article/97037 -H.G.

January 20, 2010

Now out on Museum Tusculanum Press is a new book on the subject of record covers, Coverscaping: Discovering Album Aesthetics, edited by two members of the Nomadikon group. - A.G.

January 19, 2010

If you're in Oslo on Monday (January 25th), visit the National Library's conference The Ends of Photography, which gathers a great group of scholars in what is bound to be an engaging discussion; all the presentations promise to be of high interest, but I'll mention the international guests in this brief entry: Matthias Bruhn will talk about "Hard Disks and Soft Sciences"; John Tagg's paper is titled "The Camera and the Filing Cabinet Set"; and finally, James Elkins will address nothing less than the very concept of documentary study in his presentation. -Ø.V.

January 8, 2010

Guillory on the genesis of the media concept

The latest issue of Critical Inquiry (Winter 2010) contains a long but endlessly enlightening article by John Guillory on the history of the concept of media. Noting that it was only in the later 19thcentury that the term was used with reference to technological forms of communication, Guillory goes on to explore the notion that “[t]he emergence of new technical media thus seemed to reposition the traditional arts as ambiguously both media and precursors to the media” (322). Throughout their history, aesthetic forms – or, precisely “aesthetic media,” as we are likely to say these days – such as painting, poetry and music were not considered in relation to the concept of communication, but rather to a different but no less theoretically pivotal concept: namely imitation. As a starting point for his initial discussion of the relation between medium, mimesis, and communication, Guillory points to a well-known passage in the Poetics, the one where Aristotle delineates the three ways in which imitations may differ from one another. There might be imitations in different things, ofdifferent things, and in different modes. While the latter two rather unequivocally designate the object and the genre of imitation respectively, the first case suggests a more complex reference, one that Aristotle himself skirts in the Poetics by offering a list of examples in lieu of an elaboration (colors and figures, harmony and rhythm, etc.) and by mainly focusing on the two other subjects (the objects and the modes of imitation). As Guillory so strikingly puts it, Aristotle “sets the question of medium aside, where it remained for two millennia” (323). His translators, however, would habitually interpret the phrase “in different things” [hois] as “medium” or “media.” But until the invention of new technological media such as the telegraph and the phonograph, the concept of a medium of communication had yet to surface. Guillory also intriguingly argues that the concept of communication slowly came to challenge and replace that of rhetoric, and that the invention of printing in the early modern period – perhaps the first instance of remediation – bolstered this development (324). When Condorcet, for example, celebrates printing as a form of mediation (although not in those terms obviously) in L’Esquisse d’un tableau historique des progrès de l’esprit humain (1795), he still talks about the “art of communication” rather than the “medium of communication.” A century later this will all begin to change.

This is just the beginning of Guillory’s very rich article. I won’t go into it in any more detail here, suffice it to say that it is highly recommended reading, replete with timely insights and formulations such as this one, for instance: “mediation cannot be reduced to an effect of technical media” (353). -A.G.