Ten Years Later: Re-Viewing 9/11's Suppressed Images

Richard Drew/ The Associated Press, September 11, 2001

This essay was published in late August 2011.

On this occasion of the ten-year anniversary of September 11th, we are, instead of remembering the events of that fateful day, concealing them under a mountain of American mythology. [1]

The New York Philharmonic announced in June that it will hold a memorial concert to mark the anniversary. A result of this, said Zarin Mehta, the orchestra’s president, is that the free summer concerts, held in city parks across the five boroughs for the past 45 years, must be canceled. This unfortunate undoing of a tradition of collective cultural appreciation will make way for a commemorative performance of Mahler’s 2nd Symphony, the “Resurrection.”

The New York Times noted that this is “[o]ne of the first major 9/11 cultural remembrances announced so far.” [2] Not only will many others follow, but they will be exceedingly similar in tone. They will acknowledge loss, but primarily they will celebrate resurrections. They will foreground the heroes. They will mark our resiliency, as a city and a nation. They will continue to construct a triumphal narrative of 9/11 that began shortly after 8:46 a.m. nearly ten years ago. [3]

If the recent past is any predictor, these cultural remembrances will also carry on the practice of ignoring some of the gruesome details of that date, especially the manner in which an entire category of victims perished. These victims constitute approximately 7% of those who died in New York City—they are the men and women who fell and jumped to their deaths from the North and South Towers of the World Trade Center.

The Forgotten 7%

In the United States the photos of victims falling and jumping from the World Trade Center towers generally ran in the newspapers for one single day—September 12, 2001—and then never again. [4] Those photos were deemed too painful, too much a violation of the dying moments of the victims depicted.

A similar situation occurred with the videos of falling and jumping victims. CNN, for instance, initially aired video in which the bodies were too blurry to be recognized, but quickly decided that they would not run that footage at all, and NBC broadcast an image of a jumper one time but then not again. [5]

An estimated fifty to two hundred men and women died most publicly that day [6]; they plummeted outside the Towers that were to crush to ruins everything—and everyone—inside, and yet curiously, they have disappeared from the public’s eye. In fact, charges of voyeurism, escalating to claims about the pornography of catastrophe, have led to the widespread removal of these images from the shared and readily accessible historical record. [7]

But such censorship was not always so in American journalistic history. Indeed, readers of news publications have long seen disturbing photographs of the dead and those who are about to die—all the way back, for instance, 100 years ago, to the mangled bodies of garment workers who jumped from the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory. Far more recently, New York Post readers glimpsed one of the last moments of an NYU student as she tumbled to her death, committing suicide from a high rise in 2004. [8] But no one is looking at those who fell from the World Trade Center towers. One way to account for this is to recognize the role of the triumphal myth; these particular victims don’t fit the narrative we desire to construct about 9/11 and about our nation in the aftermath.

In light of indictments of voyeurism and pornography, we realize that the act of looking becomes utterly entangled with feelings of shame. These pictures literalize our frailty and vulnerability. The call to “look away” is not simply about protecting those pictured, but also about protecting those who are looking. But as a nation that has self-censored these most horrific images, are we inappropriately selective when it comes to the victims for whom we will bear witness? In closing our eyes to the falling bodies, what else are we excluding?

Perhaps unexpectedly, the answer is that in shutting our eyes, we are also, metaphorically, closing our ears and not listening to what these images communicate. Even a visit to the museum collection that is currently available via the website for the in-progress National September 11 Museum turns up no mention of these deaths. [9] Interestingly, one audio clip in the Oral Histories category of the museum collection features a photojournalist, Catherine Leuthold, who offers a compelling if heartbreaking case for, in fact, looking at these images. Positioned right nearby as the South Tower fell, she says of that experience: “I took a picture of me in the mirror. I thought I was going to die. […] I realized later what seeing yourself in this situation meant for the people that I had taken pictures of. It was like a reaffirmation that you were actually there and that it really did happen and that it was as big as you thought.” [10]

Instead, the past decade has seen the continual non-affirmation of the falling victims. While seemingly no one wants to engage this subject, a recent novel—one of the few places, albeit a fictional space, where this manner of WTC death has been treated publicly—forces these issues onto the table, at a moment in our own history when such reflection is absolutely necessary. Don DeLillo’s Falling Man (2007) compels us to confront the ways that those falling body images—even if they have been all but removed from the record—still in fact haunt, and to consider what those images say to us now. They speak to us, ultimately, not only about the past and the events of one fateful day, but about our role in an urgent and ongoing dialogue on censorship and state control of information.

Now, nearly ten years later, we have just witnessed an eerie echo of the suppression of gruesome documentation in the Obama administration’s decision to withhold the photos of a dead Osama bin Laden from the public. 9/11 and the death of bin Laden are offered as the bookends of a story, tragic at the outset and victorious in conclusion. But these two moments are also linked by the uncomfortable suppression of information—in one case largely by public opinion, in the other by our president’s administration. Like the two beams of blue light that are projected each year from the footprints of the absent World Trade Centers towers, these acts of suppression mark their own kind of absence—an absence of memory and knowledge.

The close scrutiny of the history of the falling and jumping images may not, in the end, provide easy answers for the case of the bin Laden photos, but it does teach us about the dynamics of suppression. Taking the time to look at what has been withheld through the disappearance of the 9/11 photos reveals much about how we remember, the myths we depend on, and the dangers of this type of “moving on.”

The Falling Man

In his novel, DeLillo follows one of the survivors of the North Tower down a rubble-strewn street, through the chaos and cacophony, past the ashy landscape of lower Manhattan, and finally toward safety—to the home of Lianne, the wife from whom the survivor protagonist, Keith, had been estranged prior to the attacks, and with whom he has a young son. Set mainly in post-9/11 New York City and focused largely on the experiences of Keith and Lianne, DeLillo’s novel emphasizes that the effects of trauma aren’t only physical, as the event ruptures more than just the cartilage in Keith’s wrist; he does not walk out of the Trade Center tower a whole man, even if, in ways, his life looks more whole after 9/11 for his having reconciled with the family he’d left behind some years before. Lianne, meanwhile, finds herself fusing the public circumstances with private memories; her confused and anxious response to the terrorist attack intertwines with a trauma suffered years earlier when her father, diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, shot himself in the head. In bleeding the personal trauma into the collective suffering, DeLillo implies that despite the vastness of September 11th, despite the collective experience of death and the public coming-together in the aftermath, despite the unity that New Yorkers and Americans both felt and heard as politicians asked us to “stand together”—despite all that, DeLillo urges us to remember that collective cultural trauma comprises, engulfs, and breaks individuals.

This is made abundantly clear through the work of a minor character who plays a major role in articulating the unspeakable. As a performance artist, he travels around New York City enacting falls from buildings and other structures, “one leg bent up, arms at his sides. […] always upside down.” [11] The pose he assumes replicates the fall pictured in a photograph that was taken by Richard Drew, a photographer with the Associated Press. It portrays a man plummeting from the North Tower.

Drew’s photo, which ran on page 7 of The New York Times, among many other publications, on September 12th, is a striking, frightening image. It depicts a man vertically parallel to the Towers, and thus aesthetically in harmony with his backdrop. Frozen in the photograph, the victim is suspended forever in what some have referred to as a “swan dive.” It is—as far as the single frame of this photo reveals—graceful, and that of course is, in turn, what makes the image so ghastly. Something so horrendous has become, in a photograph, compositionally beautiful, a phenomenon Susan Sontag has discussed: “Photographs tend to transform […] and as an image something may be beautiful […] as it is not in real life.” DeLillo gestures, seemingly deliberately, to this observation, as his character Lianne thinks about the subject of Drew’s photo: “dear God, he was a falling angel and his beauty was horrific.” [12] While the public tends to recoil from this sort of union of the beautiful with the atrocious, the photograph, Sontag reminds us, “bears witness.” [13] Looking away, in the form of suppressing, becomes ethically fraught.

Like the actual man pictured in the photograph, whose identity remains unconfirmed, the performance artist works anonymously. But DeLillo also shows up a glaring difference between his art and the actuality; in DeLillo’s fictional world, readers learn this character’s name from his obituary. This is something that can never happen for the real-life victim of Drew’s photograph. Educated guesses have been made as to who that man was, but to no certain outcome. One tenacious reporter, Tom Junod, recognized the value of this image and worked, with limited success, to track down the victim’s identity. [14] If in 2003 Junod was already questioning the disappearance of the falling and jumping photos in a celebrated investigative piece, the concern only resonates more profoundly today as the ten-year anniversary reveals a firm public commitment to looking away from that 7 percent.

Moreover, the very lack of a name attached to the victim in Drew’s photo facilitates a stripping of his humanity. With no identity, that victim is no longer treated as an individual, but has become a symbol of death we will not consent to view. Notably, the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner did not officially determine death by jumping for a single 9/11 victim. [15] Formally, then, we have a whole category of deaths we can “shut our eyes to” because the official records have already done so. Yet in shutting our eyes, we also stop listening.

DeLillo’s performance artist battles against that, demanding an attentive appreciation of silence. In fact, he never talks, never explains why he performs the fall. But his silence speaks more powerfully than an explanation could; it suggests the silence of the victims who, at a literal level, went unheard. Reports from Ground Zero confirm that the falling and jumping victims could not be heard save for the sound created by the impacts of their bodies with the ground. [16] And so, and as at the Towers, the performance of the fall relies upon reaction in its witnesses, presumably those who gasp and scream as they see the unthinkable—those who give voice to silenced victims.

At least that is how it might work in the realm of fiction. In reality, the loudest voices screamed out against any acknowledgement of these images.

“That Picture Just Made Me Angry”

The falling and jumping men and women are victims of a double violation—they were murdered by terrorists and are now denied recognition by the American public. Instead of bearing witness to this particular horror, the public unleashed an angry and vocal torrent against the falling body images that ran on September 12th: Such photos are obscene; they're an invasion of the victim’s final moments; they undermine his dignity. The thunderous voices of public opinion were heard and obeyed, as they drowned those victims further in silence, despite what should have been evident. What was obscene was the attack, not these victims. The photographs don’t undermine dignity, but refusing to bear witness does.

In the past decade, there has been one film made that substantively treats these images (and which grew from Junod’s reporting), a documentary titled 9/11: The Falling Man (2006) by director Henry Singer. [17] It features irate citizens, disgusted by Drew’s photo. One reader of a local paper in Allentown, PA says of his reaction to the publication of that image: “I’m not an angry guy. I’m pretty much a very passive person. Nothing fazes me. I’m very light hearted. But that day, that picture just made me angry.” But the question remains, at whom is he angry? Was it really directed at the newspaper? More likely, he was unable to productively channel the overwhelming shock, grief, and horror experienced in the wake of the attacks. One editor interviewed in Singer’s film describes such reader reactions as “misdirected anger.” What begins as an emotional response to an image has tangible repercussions for the way we write an event into history.

Indeed, the public demand was to deny the existence of Drew’s painful image, and all others like it, despite the fact that newspaper editors describe thinking it was a Pulitzer-worthy picture, as Singer points out. But imagine if we had excised from history other agonizing images, such as Nick Ut’s napalmed girl, or even imminent death photos, like Eddie Adams’ shooting of the Vietcong prisoner. [18] Suggesting that a culture of shame surrounds the viewing of these 9/11 photos, the narrating voice of Singer’s film says, “[Junod] wanted to clear the name of all the jumpers.” The ten-year anniversary, however, makes certain an uncomfortable revelation: In place of clearing any stigma, these victims remain, instead, cleared from our sight, and this presents a threat to our collective memory.

DeLillo alludes to this suppression, and to the ferocious cries of public opinion, in one of the performance artist’s episodes, when passers-by are “outraged at the spectacle.” But they are simultaneously subject to it; the artist’s suspended body, we read, “held the gaze of the world.” [19] The communal outrage stems from the terror that scene induces, and as the performance is a simulation of Drew’s photo, this moment also gestures toward the terror the photograph produces. That photo may have captivated the world, but in the United States it only “held” us for one day. Why, since September 12th, have we betrayed that potent image? Because, in part, its power to possess scares its viewers—both in the novel and outside of it. Witnesses now too become victims as they’re arrested by this image that works a strange and tragic power over them. It forces them into a space that admits an identification with the falling man. Even if it is a most minimal identification, it acknowledges the terrible choice he may have faced: To burn or to fall? In looking away, we compromise that acknowledgement, even if we couch our actions in the language of protecting another’s dignity.

It is easier and certainly less painful to scream “You don’t be here” at DeLillo’s performance artist, as one witness does [20], than to consider the message his work helps to convey—that such images of death do have a place in public remembrance. They speak to survivors and for the dead, and they bear witness to the only public fatalities that occurred that day in lower Manhattan.

Mythologizing the Event

Of course, today rethinking that fateful date as the anniversary creeps closer, we should question that message. DeLillo’s performance artist forces us to consider what we remember and what we shut our eyes to. But is he, precisely in showing up what we repress, actually also holding us back? What about the idea of moving forward, of releasing the past, of acknowledging and honoring the grief that still exists even if certain images are censored? DeLillo’s fear, it seems, is that loss of the past is already and always ensured. As James Fentress and Chris Wickham observe in Social Memory: “the natural tendency of social memory is to suppress what is not meaningful or intuitively satisfying […] and substitute what seems more appropriate or more in keeping with [a] particular conception of the world.” [21]

But why, the performance artist seems to defiantly ask, is our conception of 9/11 unable to sustain the memory of the jumper victims? Why is that more appropriate? Why is it more proper that the dominant visual records of this history portray either images of the burning but still standing towers, or heroic scenes, like the one that echoes a historic moment of American triumph at Iwo Jima? [22] Why are the dying victims absent from our conception of an attack that took 2753 lives? [23]

In fact, the very examples of the Ut and Adams photos beg the following question: Which victims are we willing to look at? In the case of the falling and jumping photos, couldn’t we say that those images would only strengthen a national discourse of resurrection? We’ve been to the depths, we’ve seen the most unfathomable deaths—the people who plummeted—and still returned stronger as a nation. And yet our mythology doesn’t sustain these photos. Why not? Stepping into that space that allows an acknowledgement of the falling man’s predicament, we also admit a position of utter defenselessness. It may be that our mythology works better without being confronted by dire images that highlight such an extreme moment of vulnerability—moments that make us exceedingly uncomfortable. And in our discomfort we look away and thereby strengthen the narrative that has elided these victims, coarsening it into history.

Numerous examples, from the immediate aftermath right through to today, demonstrate that we do not want these images to be part of our collective remembrance. One post-9/11 event, here is new york, a gallery show organized in the weeks after the attacks, invited professionals and non-professionals alike to submit the photos they had taken on and just after September 11th. Presumably the goal was to voice our collective grief in the wake of a splintering attack—and to allay the pain of the experience by sharing its visual artifacts. There were more than 5000 photos submitted, but in the “Victims” section of the gallery website, only one depicts bodies falling from one of the towers. [24] While the organizers strove for “a democracy of photographs,” the public came back with a narrative that did not represent everyone equally.

In similar fashion, the National September 11 Museum operates an Artists Registry, a virtual gallery on the museum website, where artists, from novices to professionals, can share art created in response to the attacks. As of the end of July, the site hosts 580 individual artists, each of which has a portfolio, some showcasing just one work of art, others displaying many. There are, potentially, thousands of works in this gallery. While the registry doesn’t evince a direct repetition of the outcome in here is new york, a combination of targeted searches (on the words “jump” and “falling”) and random forays into the portfolios yielded only eight visual artists who have contributed work that overtly depicts falling bodies. (None of these are photos.) Instead, what one sees with unmatched frequency are elegiac images of the standing, if sometimes also wounded towers, and iconic symbols of our nation—the American flag, the bald eagle, the Statue of Liberty, and also the New York firefighters, who have transcended their local affiliation. [25]

We find comparable results with the web-browseable image collection of The September 11 Digital Archive, which “uses electronic media to collect, preserve, and present the history of September 11, 2001 and its aftermath” and encourages submissions from the public. Organized by the American Social History Project and the Center for History and New Media, this is another extensive website and devotes a section entirely to images. That portion is broken down further into five categories, some of which possess limited numbers of images, others of which are much larger in scope. Across all five categories—Digital Photos (the largest category with 1450 contributions), Digital Art, Artwork, Library of Congress artwork, and Thank You Rescuers—there appear to be just three images, all of which are drawings, of discernable falling bodies. Interestingly, two of them look like they were made by children; perhaps kids are not yet conditioned to the public insistence to look away. Moreover, the same iconic symbols that appear in the Artists Registry show up here in great numbers as well. The Digital Archive is affiliated with the Library of Congress, but that seems to be, currently, in limited web-accessible capacity. Yet going directly to The Library of Congress’ Prints and Photographs Online Catalog we encounter a similar pattern. A search on “September 11” yields 1086 results, while a search on “September 11 jump” returns one photograph of a victim mid-air, and “September 11 falling” returns three such photos. Each is only viewable online as a thumbnail. [26] If these major institutions and organizations reveal a trend, it’s alarming. There are, of course, other establishments that possess 9/11 photographs and art, but in terms of what the public seems to be contributing and what these institutions are making readily accessible, the 7% are hardly acknowledged.

It perhaps comes as little surprise, then, that in the past ten years, two public works of art in New York City—one at Rockefeller Center, the other at the Jamaica Center for Arts and Learning—that made concerted attempts to visualize and thereby reflect on the victims who fell to their deaths, have met with outrage from the public. Both installations were shut down ahead of schedule. Meanwhile DeLillo’s character of the performance artist may have been based on a real artist who staged a one-day performance, influenced by and evocative of the 9/11 falls, in 2005 in Chicago. In response, New York’s Mayor Michael Bloomberg called the artistic act “nauseatingly offensive” while then-Governor George Pataki described it as “an utter disgrace.” [27]

And not only do visual representations themselves encounter this extreme resistance, but text-based references to the images do as well. For instance, in 2006, 7 WTC, which had also collapsed from the attacks, was rebuilt with an art installation, a collection of written works focusing on New York City, designed by artist Jenny Holzer. Among the literary pieces Holzer selected to be part of her project was a poem by Wislawa Szymborska titled “Photograph from September 11.” It describes a photo of 9/11 jumpers, characterizing a moment of these victims’ descent, and in so doing it acts as a textual version of a falling bodies photograph. The poem, however, was removed from the project; an advisor overseeing the planning felt that certain of Holzer’s choices “would bring back images that people might want to forget.” [28] Though well meant, such efforts to aid the forgetting have worrying consequences. And yet this type of censoring behavior has occurred again and again, as both the public and administrators work to construct a story of unity, heroism, and healing—a story of resurrection and moving forward.

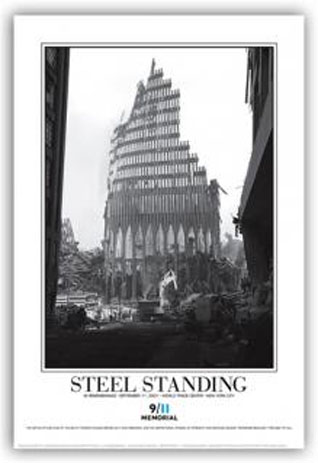

"STEEL STANDING" Photography by Anthony Whitaker

An item for sale through the September 11 Memorial and Museum encapsulates this phenomenon. The photo for purchase is called “Steel Standing” and shows a portion of South Tower that did not collapse from the attacks. The description of it reads: “This striking image of the gothic styled steel remnant of the South Towers [sic] facade serves as a vivid memorial and an inspirational symbol of strength, rebirth, courage, and defiance against terrorism because it refused to fall.” [29] The implication, of course, is that the refusal to fall is somehow more defiant and more courageous. This type of motivational language overshadows our memories of this date and tacitly affirms the accepted decision to look away from that which did fall.

As if in response, a DeLillo character makes the following comment: “From this point on, you understand, it’s all about loss.” [30] If the way forward is paved too much in the inspirational language of “moving on,” then the cultural loss—and precisely the memory of individuals’ deaths—is too dangerous, too great. Paradoxically, even as we write a history of resurrection, we also, in disquieting ways, evoke Walter Benjamin’s angel of history, who, looking back over the course of time, saw nothing but a stretch of unending catastrophe piling ever higher. Our treatment of these falling body photos threatens to toss aspects of 9/11 directly onto the angel’s mountain of indistinguishable death, as we actively disregard the individuality of those who fell. Healing, here, takes the odd form of suppressing. But as one victim’s sister says of the fact that she has no knowledge of what happened to her brother, who worked in the North Tower on the 104th floor: “The truth hurts, but it also heals.” [31]

Compelling us to envision this horrible act, DeLillo’s performance artist speaks not only for the pictured victim, but for those individuals who were not photographed, and he obliges us to remember them. He insists that we not collectively look away, because over time this blends into a cultural forgetting. He thus demands that we ask questions about the suppression of information. This is not necessarily an easy way to cope with the trauma, now ten years old, and negotiate the ongoing remembrance of 9/11. But it is the responsible way, and protects against, as with too many examples from history, state-determined myths that are circulated without regard to truth. Both Stalin and Mussolini had photographs altered, removing unwanted figures, to propagate the narratives of their choosing. This, of course, does not exist on the same scale in the US, but these examples still have a sobering effect. What DeLillo’s novel shows is that if this is the climate we live in, fiction can be a way for us to step outside prevailing mythologies and consider the effects of suppression.

Wanted – Dead, Alive or Photoshopped

On May 4, 2011, The New York Times ran an article titled “Wanted—Dead, Alive or Photoshopped.” The villainous subject of this Wild-West-meets-digital-culture headline is Osama bin Laden, who was, Obama’s administration announced, killed by US forces on May 1, 2011. [32] Despite this culmination to what has been painted as a ten-year-long story of terrorist attack and American resurrection, the most visceral part of the story, indeed the most spectacular—in the very sense of spectacle—has been withheld. President Obama will not make public the photographs taken by a Navy SEAL of the dead bin Laden.

In the absence of photographic evidence from the government many resourceful digital artists doctored old photos of bin Laden and passed them off as the official death images. They were, rather quickly, identified as fakes, and yet still they made the Facebook rounds.

Interestingly in this case, the suppression of images has been carried out by the federal government, not the public. Yet despite this distinction, the suppression of the falling bodies photos has much in common with the suppression of the dead bin Laden pictures.

If the responses in New York City on the night of May 1, 2011 are any indication, the death of bin Laden was received and heralded as a jubilant, celebratory end to the story that began almost ten years ago. Times Square and Ground Zero were crowded with revelers, carrying noise-makers and partying almost as if it were New Year’s Eve. [33] This was another moment of collective coming-together, this time for a joyous reason. But this again slips too easily into the narrative of resurrection. Not only will we prevail, but now we have prevailed. The national tendency toward creation of heroic myths crowds out the simultaneously necessary work of scrutinizing how our myths and histories are written.

Speaking not in the language of censorship or suppression but rather of good old American sportsmanship, our president said of the decision to withhold the bin Laden photos, “We don't need to spike the football.” [34] The photographs, which were taken to run facial recognition analysis in order to confirm the identity of bin Laden [35], are here made equivalent to criticizable end-zone showiness. Strangely, they are not given the authoritative weight of historical evidence even though that is precisely why they were taken.

Leon Panetta, then-Director of the CIA, advocated for making the photos available, but Obama voiced concerns for retaliatory violence should those images go public. If the idea of the images, as opposed to the actual killing of bin Laden himself, as incurring violence is at least somewhat odd, it is stranger still in light of Obama’s confident assertion that “Certainly there’s no doubt among Al Qaeda members that he is dead.” [36] The photos in this capacity can offer no extra proof to what is already known and what can already be acted upon, or retaliated against.

On the other hand, perhaps there is some logic to Obama’s argument. While Al Qaeda loyalists assuredly understand, as an objective fact, that bin Laden is dead, the President fears that exposure to a graphic reminder will ignite in those loyalists a murderous emotional reaction—one more virulent and uncontrollable than the reaction has been to the mere fact of bin Laden’s death. The President’s fears demonstrate his understanding of the very dynamic at work in the suppression of the photos of falling 9/11 victims: suppression of the images cannot undo historical fact, but it can blunt some of the outrage, shift the focus, and thereby hasten the forgetting. Accordingly, there are good reasons to suppress painful reminders with regard to our enemies, but, counterintuitively, to recognize that painful reminders should be an integral part of our own “moving forward” process.

But the debate over the bin Laden photos does not simply begin and end with concerns about what violence might be perpetrated should these images go public. In the final analysis, this may well be the most important consideration; but it is by no means the only. The reception of unadulterated information is something we ostensibly prize in this country. Yet the triumphal myth we have written over the past ten years seems to forget this principle. While it’s true that photographs of a dead bin Laden would fit the we-have-prevailed narrative, in the end, it turns out they are not necessary. The mythic narrative can come to a jubilant, triumphant conclusion regardless of the presence or absence of those photos, perhaps because the mythology itself is so embedded it does not require additional affirmative documentation.

This isn’t to say that there is reason to doubt bin Laden’s death. But if the public’s participation in the myth marks an uncritical reception of information, this is worrying. It becomes a problem, more generally, if history begins to write itself through preconceived storylines that don’t demand evidence (or that superficially accept a fake on Facebook in absence of other visual confirmation). At the least, we should always feel troubled when we know that material is being suppressed.

Photographs record—and in turn, become a part of the historical record, as the photos of Saddam Hussein’s dead sons Uday and Qusay did. Their bloodied bodies were not censored from the media. While the images of bin Laden are no doubt horrendously graphic, we find ourselves in a strange position when the state decides what we can and cannot see of our military involvements. This was the case until recently with the ban on news depictions of flag-covered coffins of dead soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. That particular suppression of images contributed to notions of American exceptionalism. It’s easy to believe we’re exceptional when we never see documentation of our own vulnerability. The suppression itself—the very absence of information—has meaning that can be misconstrued. This is so both with the images of our vulnerability as well as those that expose our strength, as presumably with the bin Laden photos.

Suppression is thus a fraught practice, and more to the point, the slope from suppression to censorship is slippery. What may appear prudent from one perspective is dangerous from another. And it is potentially more dangerous when it occurs without public knowledge (how often, we have to ask, does that happen in the US?), or even occurs in an unthinking manner by the public itself, as it adopts a censorial behavior in its raging public outcry.

“Once Upon a Time”

From Jonathan Safran Foer, Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close

Another post-9/11 novel, Jonathan Safran Foer’s Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close (2005), also treated the images of falling and jumping victims. His novel, in fact, reproduces what appear to be photo stills, fifteen in all, of one of those victims. But instead of showing the figure plummeting downward through fifteen photos to certain death, Foer runs the images backward. The flipbook, which closes the novel, depicts the victim ascending back up to the heights from which he fell.

The book's last page of text, just before the concluding flipbook, is written in the pluperfect conditional tense, as the young protagonist thinks backwards through all of his father’s probable motions on September 11th, all the way back to the known—to their last night together, September 10th, when his father told him a bedtime story, from “the end to the beginning, from ‘I love you’ to ‘Once upon a time…’." The protagonist imagines that “We would have been safe.” [37]

The flipbook images that directly follow are the visual equivalent to this textual conditional tense. In reversing the chronology, the child narrator essentially reinstates the pictured body—which has come to stand for his father, who died on 9/11 and whose body was never recovered—back into a safe place inside the World Trade Center tower.

From Jonathan Safran Foer, Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close

There is a tremendous poignancy to this reversal of events, as surely this ability to go back in time is what the protagonist ardently desires. But pressing questions also arise: Does this rewriting of the narrative reflect something sinister? Can images like these, because they are not seen and not given voice in the public consciousness, be appropriated in bizarre manners, pulled out of their context, and used in “Once upon a time” fairy tales that don’t admit the crushing realities of broken bodies? As it turns out (and forging an unexpected connection with the bin Laden pictures that surfaced on Facebook), these particular images appear to have been photoshopped, an observation made by Laura Frost of The New School, who points out that the depicted figure - instead of tumbling and flailing - holds the same position in every frame. [38]

Many critics, in vehement denunciation of the concluding photo stills, objected in particular to the way in which Foer incorporated "an indelible image of desperation and death." [39] In turn, some described the novel as profiting from grief. And yet perhaps we, the public, have created these very conditions in refusing to look at these images in any other context. They are labeled sensational and find themselves, altered and photoshopped along the way, now residing in a house of fiction because they are no longer part of our history, no longer records of our past. In its representation of the topic of the jumpers, Extremely Loud allows us to consider some of the consequences of suppression.

DeLillo offers a related episode, but moves away from the child’s perspective into the knowing vantage of adults. Lianne is horrified by her son’s insistence that the towers have not fallen: “This repositioning of events frightened her in an unaccountable way. He was making something better than it really was.” He, too, tries to reverse time, but ultimately, this invention is “a failed fairy tale.” [40]

It is perhaps easier to argue against writing a historical narrative that works through the heroic mode to the exclusion of 7% of NYC’s victims than to demand that all military photos go public; yet the analogy with the bin Laden pictures—and the fact that these, too, are not a part of the public official record—at the least raises important questions. In controlling the release of photographs, the government affirms that they are powerful tools. What agenda, we should always ask, is being served? In the case of the falling and jumping images this points us toward another question: What does this elision mean about how we remember as a nation? Photographs function as testimony. When and how do we “listen” to them?

The National September 11 Museum at Ground Zero, which will open a year from now (the Memorial affiliated with it opens this September), is in position to be the first major institution to give attention to the falling body photos and thereby act against this trend of suppression. In 2002, the Smithsonian National Museum of American History ran an exhibit called “September 11: Bearing Witness to History” (portions of this show toured nationally from 2003 to 2006), but elected not to show a single image of a falling victim. [41] But a representative for the September 11 Museum has said that “absolutely the museum plans to acknowledge” these deaths, although currently the museum will not make public what shape this acknowledgement will take—and whether or not it will be visual. [42] Will we in fact see these victims, or will we, even as the museum encourages us to remember their deaths, simultaneously look away? This is not to ignore that these are incredibly difficult images to view nor is this to say that museum-goers should even find themselves forced to look; but these are documentation of the experiences that day and should have a space in the cultural memory.

On a certain level, the construction of historical narratives always involves silences and blindnesses. But if we accept that as a fait accompli, if that’s an adequate excuse for suppressing parts of the history of 9/11, then we are dupes. We are not thinking about what those silences and blindnesses mean, yet we should be—even in cases where the public has no control over the suppression.

While the historical narrative has looked away from the falling and jumping victims for ten years, perhaps the way back in is, precisely, through more conventional narrative forms—spoken and written word. Storytelling itself may evidence the first real signs of more engaged attempts at “facing” those victims. DeLillo and Foer, of course, have tried to tackle this taboo subject in their writing, as have a few other authors. And in the 9/11 Artists Registry, which also includes text-based art—poetry, reflections, plays, and so on—a search function brings up a handful of instances of “jump” in the written works of the 580 artists. At The September 11 Digital Archive, the search on “jump” returns many more stories and testimonials. Maybe this suggests a trend, although the pervasive public language of heroism and resurrection speaks, without doubt, most volubly right now. We have to learn to listen to those who speak for the 7%, and we must not omit the visual documentation and what it says to us. The past decade has largely written these victims out. That needs to change—and there is still time.

Despite the public presentation of a decade-long story that moved from tragedy to triumph, the “9/11 narrative,” regardless of bin Laden's death, has not concluded. “Once upon a time” is not a suitable framework for this ongoing history. The suppression of the images that document it is not an acceptable way to tell it.

NOTES

[1] James Young, in characterizing historian Martin Broszat’s observation, has written: “in their references to the fascist era, monuments may not remember events so much as bury them altogether beneath layers of national myths and explanations” (1993, 5).

[2] Wakin (June 27, 2011).

[3] As of late July, various similar events had been announced. For example: A choral group will be performing in Washington, D.C. “with a program to uplift and inspire” (accessed July 27, 2011) and a 5K commemorative race in Colorado is called the American Heroes Run. Their website states, “No politics; just patriotism” (accessed July 27, 2011).

[4] Tom Junod, writing for Esquire magazine (Sept. 2003), first reports on this, especially as regards one particular falling body photo that was widely printed on the 12th: "The next morning, it [...] appeared in hundreds of newspapers." I will return to Junod's work later. See also, for instance, Barbie Zelizer, who offers this information in About to Die: How News Images Move the Public (2010), where she focuses on the temporality of photography with regard to historic journalistic images that capture a moment shortly before the subject’s death. She adds, “By the weekend [after September 11, 2001, these] images of people about to die were virtually gone, appearing in very few of the newsmagazines, retrospectives, or other overviews of that first week’s events” (47).

[5] Junod and Zelizer (43) report on CNN; The New York Times reports on NBC (Rutenberg and Barringer, September 13, 2001).

[6] The New York Times gave a conservative tally of 50 jumpers, based on the bodies they could count in a review of footage and photos they had access to. USA Today, using footage and photos, as well as eyewitness accounts and other evidence, estimated “at least 200 people” (Cauchon and Moore, September 3, 2002). The higher figure is thought to be the more accurate, which means that approximately 7.3% of those who died in the WTC attacks were falling or jumping deaths. Of note, the federal investigation into the collapse of building 1 and 2 of the World Trade Center analyzed footage of jumpers, not to learn about the jumpers themselves, but for the purpose of understanding the progression of the fire and its destruction of the buildings. The New York Times quotes Michael Newman, a spokesman for the National Institute of Standards and Technology: “What data we have in this area are being used to better understand the movement and behavior of the fire and smoke in the towers” (Flynn and Dwyer, September 10, 2004).

[7] While a limited number of falling and jumping pictures can be found online, by and large, these photos do not exist in public commemorative spaces and hardly ever show up in the types of sources that traditionally command authority with regard to historical evidence and which, long term, determine a certified record of history.

[8] New York Post, March 10, 2004. Cover image, “Suicide,” by Scott Schwartz. Zelizer notes that some critics and journalists denounced the publication of this photo (51), though the decision to run it at all, especially in a paper with the 7th highest circulation in the country, reveals that the 9/11 falling body images—and their nearly immediate suppression from the public eye—didn’t result in a moratorium on other falling body photos.

[9] Over the course of the week of July 6 to July 13, 2011, this author spent up to six hours each day on the website for the National September 11 Memorial and Museum (www.911memorial.org), listening to audio, reading text, and looking at images, timelines, renderings of the planned museum, and so forth. Beyond the museum collection portion of this extensive site, one finds few references to these deaths. I will return to this as it pertains to another section on the website, the Artists Registry. Research on the registry was conducted on July 30, 2011.

[10] The website for the National September 11 Memorial and Museum.

[11] DeLillo 2007, 33.

[12] DeLillo 2007, 222.

[13] Sontag 2003, 76.

[14] Junod’s 2003 article, “The Falling Man,” charts the early resistance to 9/11 falling body imagery as the author tries to find the identity of the man in Drew’s photograph. Junod retraces the work of journalist Peter Cheney from The Globe and Mail, who thought he had identified the “falling man.” Junod discovers that Cheney’s finding is likely incorrect and identifies another man, a sound engineer from Windows on the World, as possibly the victim pictured in this image.

[15] A spokesperson for the office says: “We don't like to say they jumped. They didn't jump. Nobody jumped. They were forced out, or blown out” (quoted in Junod).

[16] Many have related that the sound of the bodies slamming into the ground was incredibly loud. Two brothers, Jules and Gedeon Naudet, French documentary film makers, were working on a project on New York firefighters. They were nearby and on site at the Towers with the FDNY that morning. Their footage records the sounds of jumpers’ impacts with the ground. The Naudet brothers’ film is titled 9/11 (2002).

[17] Singer has made the most thorough film to date, although a very limited number of other films have included small amounts of footage of these victims. In addition, in 2006 Kevin Ackerman directed an 11-minute-long dramatization about a Windows on the World employee and the conditions that may have led to jumping. It was shown at the Tribeca Film Festival, where organizers had to provide Ackerman with a bodyguard after he received hate mail in response to the film (Riley).

[18] In fact, one of the subjects in Singer’s film, an editor at The Morning Call, even compares Drew’s photo to Adams’ Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph.

[19] DeLillo 2007, 33.

[20] DeLillo 2007, 164.

[21] Fentress and Wickham 1992, 58-59.

[22] Of note, and in keeping with the “story of 9/11” that is being written into history, Thomas E. Franklin’s image - the echo of Iwo Jima - was short-listed for the Pulitzer Prize and a photo, by Steve Ludlum for The New York Times, which depicts the wounded yet standing towers, was awarded the Pulitzer.

[23] Others have noted the post-9/11 dominance of the heroic. See, for instance, Singer’s film, where the narrator says, “the world preferred to remember the heroic images of the rescuers and how the American spirit had prevailed.” In “Still Life: 9/11’s Falling Bodies” (2008), Laura Frost responds to “positive” approaches of memorialization, as she discusses the temporalities of photography, trauma, and narrative, in her analysis of post-9/11 literature that “refuse[s] to perform that imaginative work” of delving into the experience and “larger symbolic” significance of the falling victims (196); works that handle “9/11 imagery gingerly,” she says, sustain “the myth of American invulnerability” (200). Susan Faludi’s The Terror Dream (2007) provides an interesting take that connects the attacks—and subsequent feelings of American impotence—with a cultural resurgence in traditional notions of the dominant male and the helpless female. The death toll is reported in The Daily News (June 18, 2011).

[24] See www.hereisnewyork.org (accessed July 31, 2011) and Here is New York: A Democracy of Photographs (2002); Junod. The book that grew from this event, which consists of almost 1000 photos to “give the most coherent sense of the whole” (9), also has the same one picture from the “Victims” section of the website and no other falling body images.

[25] http://registry.national911memorial.org/ The work of two artists encountered for this research is abstract enough that it cannot be easily labeled falling or jumping victim artwork; it is hard to tell if the figures in this art represent these particular victims. Another artist has posted YouTube video, but the videos do not load through the registry. Leaving the Artists Registry, going directly to YouTube, and searching for these videos does yield one that has two photo stills, on screen for a few seconds, of falling victims, but for whatever reason these are not accessible through the registry.

[26] Both The September 11 Digital Archive and the Library of Congress online catalog were accessed by this author on July 29, 2011. The 9/11 Digital Archive possesses publicly viewable collections, which were searched for this article in the interests of gauging what images are most readily accessible on this subject; but one can also register for a “researcher’s account,” which gains access to other content, such as personal notes. The first three categories in the Images section are contributions “from site visitors.” The website also explains that organizers still accept contributions from the public, but the website stopped being updated in June 2004. The Library of Congress artwork, through the Images section of the 9/11 Digital Archive, contains no falling or jumping victim art, though does have a Reuters photograph of people crowded at windows high up in one of the towers. The American Social History Project is at the City University of New York Graduate Center and the Center for History and New Media is at George Mason University. The Library of Congress search on “jump” revealed two photos that apparently include the remains of jumpers, though this aspect is not visible in the thumbnail image available on the site. See http://911digitalarchive.org/gallery_index.php and http://www.loc.gov/index.html.

[27] On the New York City works of art: Both occurrences were covered in multiple New York City newspapers. See, for example, The New York Times, “After Complaints, Rockefeller Center Drapes Sept. 11 Statue” (September 19, 2002) and the Daily News, “New Furor Sparked by Falling-Bodies Art” (September 21, 2002) and “WTC Display Yanked after Uproar” (September 25, 2002). On the Chicago artist: See Camper (July 10, 2005), who quotes Bloomberg and Pataki, and refers to the event as a “performance-cum-photo shoot.”

[28] Klara Silverstein quoted in Collins, The New York Times (March 6, 2006). Frost provides a more developed reading of this incident as well as the poem itself. Her article also briefly references Paul Chan’s 1st Light (2005), a work of art that included moving silhouettes of people falling. While Chan’s art may represent an act of “looking toward” the falling and jumping people, it still does so only obliquely; the work does not explicitly reference 9/11, these are not photographs, the art is rather fantastical (cars and cell phones float into the sky), and the setting of the scene evokes a space that is more suburban than it is Manhattan. Though this could be a comment on how the American public has treated the memory of these victims, Chan himself won’t make that move; he states that his art is not political, and deems political art “ineffective” (Holland).

[29] Both the image (photo by Anthony Whitaker) and its description were accessed here July 7, 2011.

[30] DeLillo 2007, 60. This comment is spoken in discussion of Alzheimer’s by a doctor who accepts this particular type of loss, that is, into dementia; but as we know, DeLillo’s novel analogizes the private disease and the public attacks, and thus this statement simultaneously harbors ominous social and historical meaning.

[31] Suzanne McCabe quoted in Flynn and Dwyer, The New York Times (September 10, 2004).

[32] The local date of bin Laden’s death was May 2nd; it was still May 1st in the United States.

[33] For photos, see the Village Voice (accessed May 8, 2011).

[34] Obama said this during an interview with Steve Kroft on CBS’s 60 Minutes (air date: May 8, 2011).

[35] Obama addressed this during his interview. See also, “The Death of Osama bin Laden,” The New York Times (Updated May 9, 2011).

[36] Interview with Steve Kroft, CBS’s 60 Minutes (air date: May 8, 2011).

[37] Foer 2005, 326.

[38] Frost 2008, 194. Frost provides an extended analysis of Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close. Also, a related aside to my reading of Foer: Zelizer discusses what she terms the “as if,” or the visual subjunctive in journalistic photography. While her analysis addresses single images (not series of images run in reverse), her characterization still has value here: the “as if” allows “what is depicted [to be viewed] in an interpretive scheme of ‘what could be’ rather than ‘what is’” (14).

[39] Hughes, The Wall Street Journal (March 18, 2005).

[40] DeLillo 2007, 102.

[41] This point was confirmed in an interview (July 11, 2011), conducted by this author, with Shannon Perich, a curator in the Photographic History Collections who worked on this Smithsonian exhibit, which was open at the museum from September 2002 to July 2003.

[42] Amy Weisser, Director of Exhibition Development, interview with this author (July 8, 2011).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

9/11. Dirs. Jules and Gedeon Naudet. 2002.

9/11 Commission Report: The Final Report of The National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. New York: Norton, First Edition.

9/11: The Falling Man. Dir. Henry Singer. Based on article by Tom Junod. 2006.

“After Complaints, Rockefeller Center Drapes Sept. 11 Statue” The New York Times.

(September 19, 2002). Accessed March 13, 2011.

Benjamin, Walter. “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” Illuminations: Essays and Reflections. Ed. Hannah Arendt. Trans. Harry Zohn. New York: Shocken Books, 1968.

Bertrand, Donald. “New Furor Sparked by Falling-Bodies Art.” Daily News. September 21, 2002. Accessed June 1, 2011.

_____. “WTC Display Yanked after Uproar.” Daily News. September 25, 2002. Accessed June 1, 2011.

Camper, Fred. “IDEAS, Is Art Defaming 9/11 Deaths?” Newsday. [Nassau and Suffolk Edition]. July 10, 2005. Accessed March 4, 2011.

Cauchon, Dennis and Martha Moore. “Desperation Forced a Horrific Decision.” USA Today. September 3, 2002. Accessed March 6, 2011.

Collins, Glenn. “At Ground Zero, Accord Brings a Work of Art.” The New York Times. March 6, 2006. Accessed June 1, 2011.

DeLillo, Don. Falling Man. New York: Scribner, 2007.

Dunlap, David W. “Wanted—Dead, Alive or Photoshopped.” The New York Times. May 4, 2011. Accessed June 28, 2011.

Faludi, Susan. The Terror Dream. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2007.

Fentress, James and Chris Wickham. Social Memory. Cambridge: Basil and Blackwell, 1992.

Flynn, Kevin and Jim Dwyer. “Falling Bodies: A 9/11 Image Etched in Pain.” The New York Times. Section A; Column 5; Metropolitan Desk. September 10, 2004.

Foer, Jonathan Safran. Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2005.

Frost, Laura. “Still Life: 9/11’s Falling Bodies.” Literature after 9/11. Eds. Ann Keniston and Jeanne Follansbee Quinn. Routledge: New York, 2008.

Here is New York: A Democracy of Images. Eds. Alice Rose George, Gilles Peress, Michael Shulan, and Charles Traub. New York: Scalo, 2002.

Holland, Christian. Review of Momentum 5: Paul Chan @ ICA. Big, Red & Shiny. Issue 29 (October 23, 2005). Accessed July 17, 2011.

Hughes, Robert J. "Bookmarks." Review of Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close. The Wall Street Journal. March 18, 2005. Accessed April 13, 2011.

Junod, Tom. “The Falling Man.” Esquire 140 (originally published Sept. 2003): 176-99. Reprinted online. Accessed February 4, 2011.

“Man's Death from World Trade Center Dust Brings Ground Zero Toll to 2,753.” The Daily News. June 18, 2011. Accessed July 30, 2011.

Obama, Barack, President of the United States. Interview with Steve Kroft. 60 Minutes. CBS. Air date May 8, 2011.

Perich, Shannon. Interview with Lauren Walsh about absence of falling body images in Smithsonian exhibit. July 11, 2011.

Riley, Rowan. “Are Audiences Ready for ‘The Falling Man’?” The Huffington Post. May 4, 2006. Accessed July 16, 2011.

Rutenberg, Jim and Felicity Barringer. “AFTER THE ATTACKS: THE ETHICS; News Media Try to Sort Out Policy on Graphic Images.” The New York Times. September 13, 2001. Accessed July 14, 2011.

Sontag, Susan. Regarding the Pain of Others. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003.

“The Death of Osama bin Laden,” The New York Times, Updated May 9, 2011. Accessed June 27, 2011.

“The Falling Man.” Dir. Kevin Ackerman. Prods. Kevin Ackerman with Rick Ojeda and Robert Sanford. 2006.

Wakin, Daniel J. “Philharmonic Announces Free Concert to Mark 9/11.” The New York Times. June 27, 2011. Accessed June 29, 2011.

Weisser, Amy. Interview with Lauren Walsh about falling body representations in the National September 11 Museum. July 8, 2011.

Young, James A. The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning. New Haven: Yale UP, 1993.

Zelizer, Barbie. About to Die: How News Images Move the Public. New York: Oxford U Press, 2010.