About Class Photos

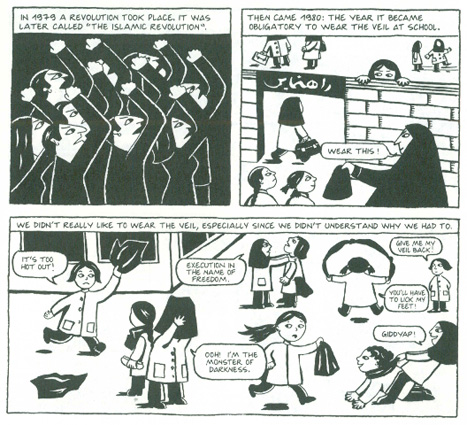

"This is me when I was ten years old," says Marji in the first frame of Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis, a memoir in graphic form, and we see a little girl, simply drawn, wearing the veil and looking serious, if not glum. [1] The present tense confirms that we are looking at the drawing of a fractured photograph through which the narrator introduces herself. The portrait of the ten year old Marji is merely a detail of a class photo shown in the next frame in which she is not visible: all we can see is part of her left arm and the right hand that crosses over it as she assumes a pose identical to that of the other four girls. "You don't see me," she tells us as she names the other four from left to right. All five wear the veil and all look equally distressed although, with a few lines, Satrapi is able to convey physiognomic differences and a range of facial expressions.

Why use a class photo by way of introduction? And why is Marji invisible within it? Satrapi's opening frames tell us a great deal about this most unremarked genre of vernacular photography which, within the visual structure of the comics medium, underscores the ideological transformation effected by the Islamist Revolution that interrupted Satrapi's childhood. The rest of Persepolis plays out the uneasy and sometimes violent oscillation between a "me" that can be visually captured in an image and the evasive "you don't see me" - an oscillation between the subject of totalitarianism and the rebellious "I" who disappears in the gutter between frames. Class photos, even under politically less authoritarian circumstances, dramatize precisely the individual child's struggle between singularity and ideological interpellation. The extreme situation drawn by Satrapi merely accentuates some of the general features of this vernacular visual genre.

Taken by commercial photographers with seemingly few if any artistic aspirations and little desire to deviate from formulaic representations, class photographs share the same general characteristics. A group of students, standing or sitting on benches or by their desks (or standing outdoors, in rows, near the school building) all face forward and look at the photographer. The group is usually photographed head-on, generally through a wide-angle lens. Most class photos distinguish themselves from other institutional group photos by the central position of a teacher, around whom students are arranged. The teacher's presence, like the photographer's, serves as a disciplining force, enjoining the children to assume postures and gazes that demonstrate their acquiescence to a group identity imposed through their membership in their class. In Satrapi's memoir, the unforgiving teacher appears in the fourth frame, holding the veil and instructing the little girls to "Wear this!"

Although not fully visible in the image, the contextual matrix of the class - the school accredited by the municipality or state - plays a key role. Schools are the institutions that teach children to read and write, and which provide them with elements of a national literary and scientific culture and its versions of history. They are also the sites that instruct them in rules of acceptable behavior and morality, tutor civic responsibility, and instill respect for authority and the established economic order. While aided in this task of ideological inculcation by other institutions - the family, the law, the media, and the arts - they are primary agencies in shaping and reinforcing values, outlooks, beliefs, and myths that constitute citizenship in the society where they are located.

Class photos, in this regard, like school diplomas, can be seen as a form of certification - confirmation of grade level, grade ascendancy, and of participation in a trajectory of socialization defining citizenship and national belonging. Each image is visual evidence of this commonality among the depicted group of children, a commonality often enforced and highlighted by the wearing of uniforms, dress and hair codes, and by other means of minimizing or erasing differences. Few markers of difference are visible in class photos, and Satrapi, through the idiom of comics, is able to emphasize how uniformity is imposed and difference discouraged, even punished.

The assimilating pull towards sameness in setting up and posing in these photos makes the possibilities of subversion minimal even within pictures taken in less repressive political settings. Children may try to fool around before or even while the photos are being taken, but the class photos that survive are no doubt the ones that record the most uniform deadpan look on all the faces. Class photographs do more than just to record children's ideological formation: they actually instantiate the force of the institution as it interpellates the individual into a trans-individual group identity. And they certify that interpellation. The school photographer's camera, as such, is one of the technologies of socialization and integration of children into a dominant world-view. By staging the school's, and the society's, institutional gaze, class photos both record and practice the creation of consent.

In the large double frame at the bottom of Satrapi's first page, we see the girls' rebellion against the wearing of the veil that forms the background against which the compliance registered in the class photo must be read. "We didn't really like to wear the veil," the narrator tells us, and individual children, wearing uniforms but sporting different hairstyles, gestures and facial expressions, run around the school yard playing hide and seek, jump rope and even "execution" with the piece of black fabric. The school building with its foreboding black windows remains visible and the games occur in a space external to it, just as in the frame above, girls can fool around outside the school walls but must comply with the teacher in the foreground, inside. Satrapi's expressionist drawing style, relying entirely on bold blacks and whites, underscores this opposition: the bottom image where the children play and fool around has lighter, thinner lines, more white, while the class photo, featuring the uniformity of the veil, is thicker, darker, almost entirely black.

Why does Satrapi begin her story with a class photo? Their sameness and ubiquity would seem to make school photos largely unremarkable. How, then, can we explain their pervasiveness in family albums, their common display on memorial websites and at reunions, and their frequent reproduction in communal histories and in memoirs? Certainly, in spite of their conventionality, they do provide some contextual information about the school, the historical moment, and the cultural values of the time when they were taken. But in most cases that information is minimal and the images remain interchangeable and opaque. And yet, as Satrapi shows, they can serve not just as vehicles of narrative and memory, but also as political media of protest and resistance. How can we explain this capacity?

If we read class photos as a subset of group portraits -- paintings and photographs of guilds, army units, clubs, unions, and youth groups - we might speculate on the associations they evoke. We might see them in the terms introduced by art historian Aby Warburg who in his "Mnemosyne Atlas," mapped a large set of "pre-established expressive forms" that carry and transmit affect across time, constituting a trans-generation memorial repertoire in visual form. [3]

If class photos fall into such a category of expressive forms then their "emotional life" [to use Jill Bennett's term] would be transmissible. [4] By recalling the subordination of individuality to group membership and the incorporation into a social assemblage, they would convey both the desire to belong to the group and the resistance against the coercive submersion of the individual within a class collective. Indeed, this tension between individuality and trans-individual anonymity structures the emotional life of class photos. Since like all photos, moreover, class photos freeze a moment in time, they serve to measure change over time, and to recall past incidents, when they are viewed and reviewed years, perhaps decades, later. They thus not only become potent media for anyone wishing to memorialize and mourn a world of yesterday but also effective mnemonic aids helping to identify particular living classmates - as well as age mates who have disappeared (or been violently removed) from our midst. As documents that carry incontrovertible evidence of past existence and previous acceptance, they assert "we were here" and become powerful emotive as well as political vehicles combating forgetting and the erasure of violence and the exclusion of some members from the group.

It is this very inherent emotional and political life of class photos that Satrapi is able to mobilize in the project of underscoring the violence of the Islamist revolution and her resistance against the loss of individual freedom. Throughout the two volumes of Persepolis, Marji's rebelliousness is never squashed and school remains the site of her resistance. In school in Iran, she stages her resistance to the veil and the conformity demanded of girls and women by the Islamist regime. Later, in Vienna, she rebels against school rules and against the different constraints on individual freedom operative in the West.

In addition, the very ordinariness and ubiquity of class photos enables them to become privileged media of memory and mourning for those who become separated from the group. "From left to right: Golaz, Manshid, Narine, Minna," Marjane names her classmates individually. In the course of the memoir, some classmates will be persecuted and killed, others will comply with the regime and others still will continue to rebel and, along with Marji, to assert their freedom. When Marjane says, "you can't see me," she is activating the emotional life of class photos, both the struggle between individuality and conformity that they stage, and the sites of mourning they can so effectively become. In the medium of comics, the gutter becomes what Warburg calls "the iconology of the interval," that space "between thought and action" where intense emotion can surface and be felt. Class photos drawn in comics form: relying on both genres, Satrapi can provoke an immediate and layered emotional response on the part of her reader.

[1] Marjane Satrapi, Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood (New York: Pantheon, 2003) and Persepolis 2: The Story of a Return (New York: Pantheon, 2004).

[2] On Satrapi's style, see Hilary Chute, "The Texture of Retracing in Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis," WSQ 36, 1&2 (Spring/ Summer 2008), 92-110.

[3] Aby Warburg, Der Bilderatlas MNEMOSYNE, Martin Warnke (ed.), Berlin 2003, 2nd printing.

[4] Jill Bennett, Practical Aesthetics: Events, Affects and Art After 9/11 (forthcoming).